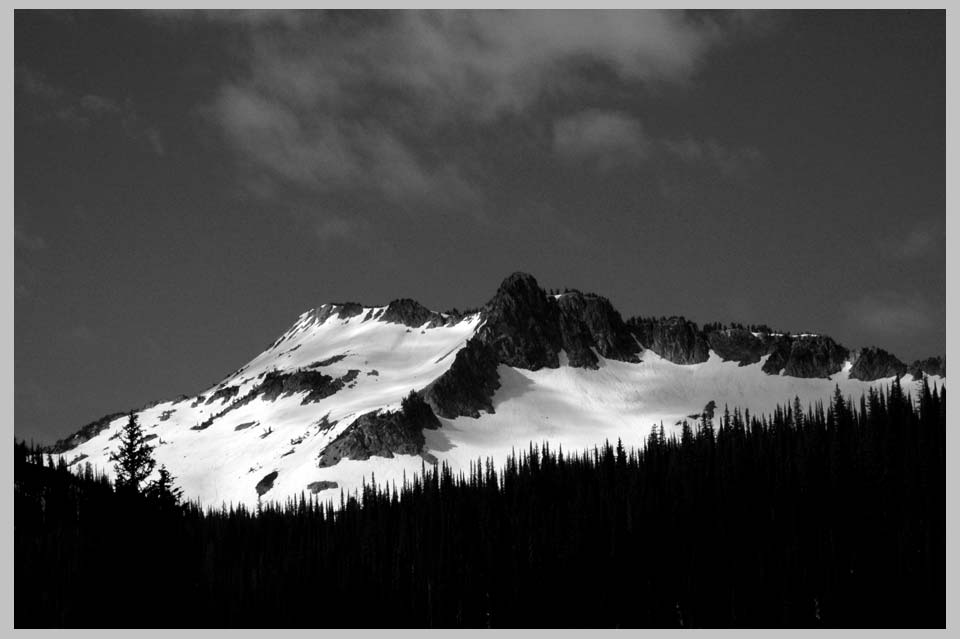

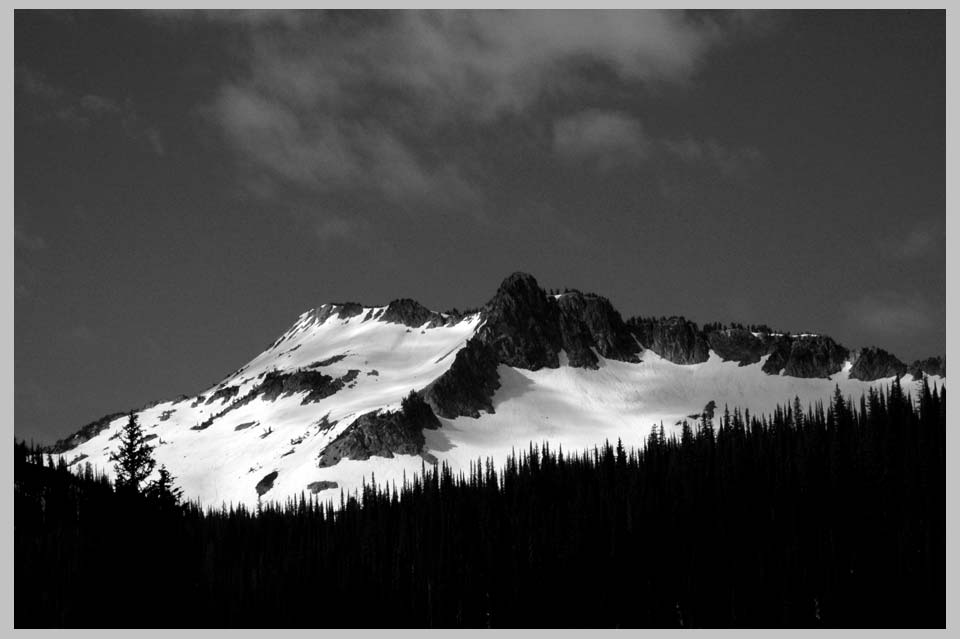

Above Hidden Lake, East Eagle Valley , South Wallowas . . . Notice the

healthy 4th of July snowpack! In an area that receives almost no rain

from June through September, that snow is 'money in the bank.' All

life in these mountains, from trees to nutctrackers—as do ranchers

further down stream—depends on it.

On the road in the American Northwest.

ON THE FRAGMENTATION OF

NATURAL WATER CYCLES

I have to admit, that I do not really know first hand what

a natural water cycle is because I have never lived in a

culture nested wholly within one. But I do without a doubt

know what a natural water cycle is not. And let it be said

straight away, that I do not like what I see, both in the parts

of the European Alps that I know well, and those areas of

the Northwest that I am presently exploring. I do not like

this recurrent pattern of the radical fragmentation of natural

water cycles: the dam the river; break the flow; fill the

reservoir; the incessant watering of questionable monocultures.

And, most importantly, I do not like the, in my view, utterly

futile attempt to control as if it were a neat, orderly, precise

Swiss system of trains, both the rhythm and the quality of

movement of the truly rich and chaotic complexity of the

water cycle as a living whole.

The results stand like a huge warning sign before us

and are unequivocal. For me personally, the evident,

straight forward fact is that, in the Reuss/Rhein watershed

of the Alps where I've worked for many years intensively,

the salmon stopped running in 1958; And now, by some

strange twist of fate, the part of the great Columbia watershed

in which I'm now focusing much of my attention, the South

Wallowas, the salmon also stopped running that same year.

Those are facts. But in a far more subtle and tragic way, some

vast essentially unknowable natural movement has been halted,

has stopped turning as it were, as if a heavy wrench were

thrown into the delicate spokes of a finely trued wheel. So

the movement of the cycle fragments, breaks up into out of

synch, partial, incomplete, disharmonious smaller cycles.

The result is that all life that depends not just on water, but

the flow of a watershed as a whole, begins to suffer—one

species at a time—begins to pull back, dry up, vanish.

("Vanish" here is not an exaggeration: In both areas

mentioned above—the central Alps and the South Wallowas—

there is no recovery plan for salmon, which ipso facto means

that they are effectively being erased from consciousness.)

Nobody intended this to happen. But it is real, and taking

place as we speak. So why do we not let the from the human

perspective infinite wisdom of the Earth itself heal our

mistakes? Why do we not make use of our uniquely human

freedom to stop doing something when we discover it is inherently

contradictory or wrong? Indeed, it may also be argued that

every contradiction against the principles of natural limits

comes together necessarily with the ethical imperative of

taking immediate and decisive action to deal with the

contradiction head on, and thereby restore balance and

harmony. The answer to the why is as simple as it is difficult

to confront and is repeated on every single line of dialogue drawn

in the contemporary sands of environmental contention: on

one side of the line, there exist powerful, vested, moneyed

interests which are totally committed to sustaining the

contradiction to the bitter end. In other words, the natural

world is now unfortunately managed by those who are

primarily concerned not with the flow of water, but with the

flow of cash. But if what I say is true, that we are dealing

here with fundamental contradictions going squarely

against the grain of nature's way, then ultimately, regardless

of what we do, the vast infrastructure built upon these shaky

foundations will sooner rather than later fall apart and

collapse.

Why might this be so? Simply because, in the view represented

here, Nature—as in a telling and remarkable way our own moral

conscience—above all else, abhors contradiction.

|

|

| back to Picture/Poems: Central Display | go to P/P Photoweek: Archive |or go to last week's PhotoWeek pages |

| Map | TOC: I-IV | TOC: V-VIII | Image Index | Index | Text Only | Download Page | Newsletter | About P/P | About Cliff Crego |

Photograph by Cliff Crego © 2008 picture-poems.com

(created: VIII.3.2008)